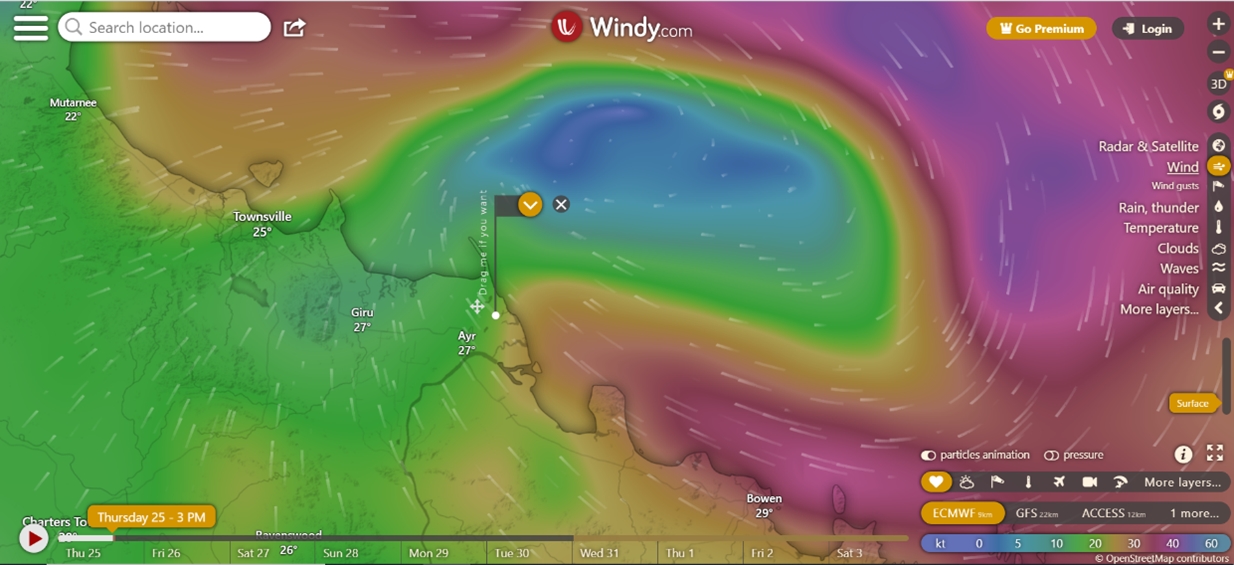

A category three cyclone swept through Queensland, Australia during a three-month deployment of two Origin 600 ADCPs in January 2024. This blog looks at the data gathered and how they performed during this unexpected weather event.

This report analyses Origin 600 ADCP data from a three-month measurement campaign at the Australian Institute of Marine Science’s (AIMS) site at Cape Cleveland, near Townsville, Queensland Australia. Two Origin® 600 ADCPs were deployed powered by external battery packs in warm, shallow water, and the measured currents show excellent agreement between the two devices.

In addition to measuring currents in typical tidal conditions, the deployment coincided with the passage of a cyclone over the site and the effect of this on the current was quantified by both ADCPs. Despite a significant amount of biofouling synonymous with warm, shallow coastal sites, the performance of the ADCPs was not significantly impacted by this over the duration of the deployment.

The data demonstrates the ability of Origin 600 to accurately and consistently measure currents over a long period in shallow, warm water, despite abnormal weather.

Introduction

Two Origin 600 ADCPs were deployed at the Australian Institute for Marine Science (AIMS) site at Cape Cleveland in November 2023 and recovered in March 2024. The purpose of the deployment was to provide site characterisation and to prove technology integration with multiple sensors.

While Origin 600 has a maximum profiling range of over 60 m, the AIMS site offered an opportunity to stress test the ADCP in much shallower water. As such, two Origin 600s were deployed at sites with a nominal depth of only around 8 m. The first site, labelled C0A, was designated a control site, while the other site (I0A) was designated as an influence site. Figure 1 shows a satellite image of Cape Cleveland, with the locations of C0A and I0A. These labels will be used to refer to the two ADCPs through the rest of this report.

A further challenge of the site was its relatively warm waters; warm, shallow water often results in significant biofouling, which can degrade the performance of the instrument over even short deployments. A further aim of this trial was therefore to characterise any degradation in performance due to biofouling.

Configuration

To optimise the data output of the deployments, both ADCPs were configured in a dual‑schedule mode so that both waves and currents could be measured. The former involved a 20 minute burst of pinging at 4 Hz repeating once per hour (schedule A), while currents were sampled using two minute bursts at 1 Hz every ten minutes (schedule B).

Due to the intensive nature of the sampling, external batteries were used with both ADCPs to allow data to be acquired for the duration of the deployment. The two Origin 600 ADCPs logged the data to industry‑standard PD0‑format data files that were downloaded following recovery of the devices. Following initial quality control using the Origin Viewer software, tools available within the Origin message deserialiser library (https://github.com/Sonardyne/origin-message-deserialisers) were used to write a bespoke pipeline to process the PD0 format data. This library provides decoder tools for all data formats provided by Origin ADCPs, including PD0, and Sonardyne’s A‑gram and B‑gram proprietary ADCP data formats.

Analysis of currents

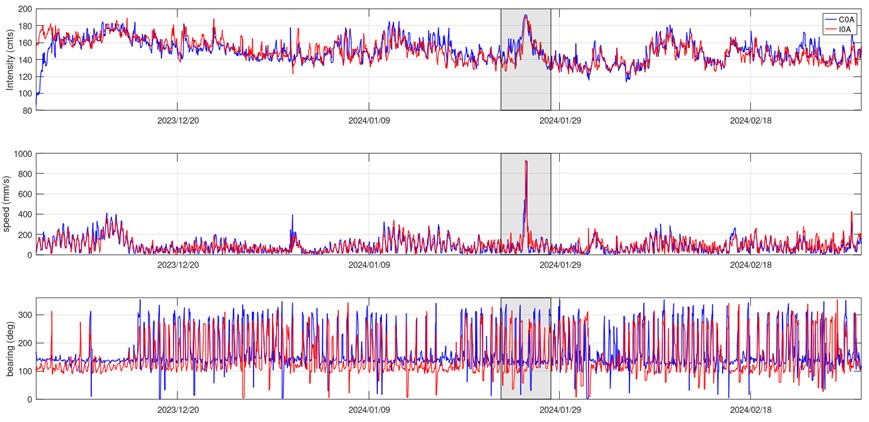

Figure 2 shows the average backscatter intensity and water speed captured over the course of the deployment for both C0A and I0A Origin 600 ADCPs. The current speed and directions were calculated by averaging the data over each burst period. Cells inside the blanking distance, within the near‑field of the transducers, and near the surface were excluded from the averaging to mitigate the effects of contamination from e.g. sidelobes.

As is evident there is generally excellent agreement between the two ADCPs in terms of backscatter intensity, water speed, and direction. This demonstrates that despite the challenges of magnetic heading sensor calibration, deployment procedures, and environmental factors, internally‑consistent ADCP results can be achieved with sufficient care and processing techniques.

The agreement between the two Origin 600s is best demonstrated when Cyclone Kirrily (a Category 3 cyclone) passed over the area on 25th January. The response can be seen in both ADCPs’ data through short term anomalies in several of the measured parameters. First, a peak is observed in backscatter intensity, potentially due to increased loading of the water column with suspended sediments or bubbles caused by waves breaking. This loading is at its maximum during the cyclone, but other peaks are present throughout the deployment.

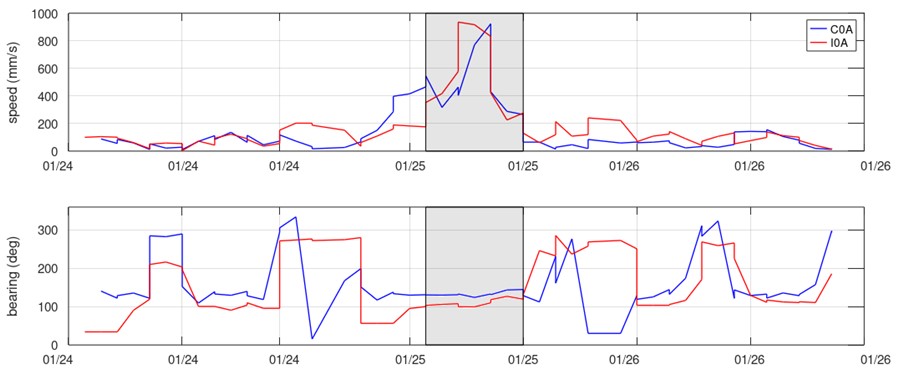

There is also a pronounced spike in horizontal water speed corresponding with the passage of the cyclone. While the data shown in Figure 3 shows a maximum depth averaged speed of approaching 1 m/s (observed consistently in both ADCPs), the maximum instantaneous speed recorded during the passage of Cyclone Kirrily exceeded 2 m/s. This further demonstrates Origin 600s ability to measure fast flowing water in challenging conditions.

Top: Backscatter intensity in (arbitrary) counts; C0A data is in blue, I0A data in red.

Middle: Current speed in mm/s.

Bottom: Current bearing in degrees.

In all plots, the grey area indicates the week during which Cyclone Kirrily occurred.

The direction of the currents shows similar behaviour between the ADCPs; however, there is a systematic shift of approximately 30˚ between the two sites, likely due to the different local land topology at each location. The general pattern of currents measured at the C0A site run ESE‑WNW, while at the I0A site currents run in a SE‑NW direction. It is interesting to note how during Cyclone Kirrily, the expected current bearing of approximately 280˚ reversed to 100˚, demonstrating the power of this natural environmental phenomenon.

Analysis of Origin 600 environmental sensor data

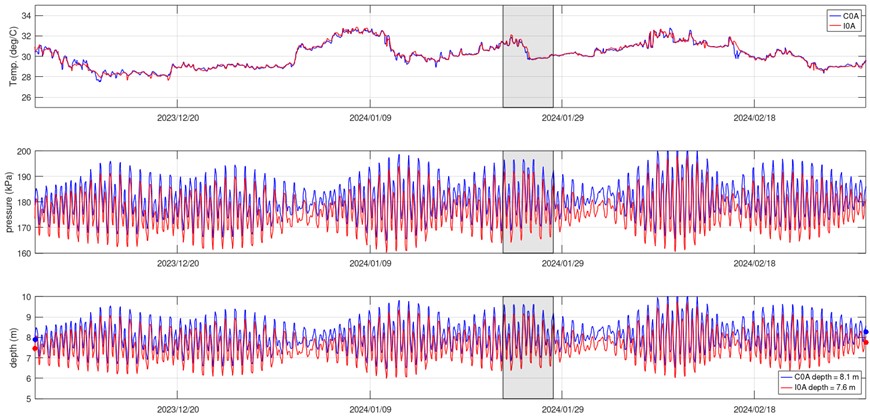

Origin 600 contains inbuilt temperature and pressure sensors; these readings are displayed in Figure 4. A similar processing pipeline to the current data was applied to these environmental sensors, namely taking 20‑minute averages over the whole three‑month deployment period.

As most of the measurements were made during Austral summer, the water temperature is quite high, between 28 and 32 degrees Celsius. The spring/neap tidal cycle is also clearly visible in the pressure measurements as is the semidiurnal nature of the tides. No significant change in pressure was observed during Cyclone Kirrily, though large fluctuations may be averaged out during processing the data into 20‑minute averages.

Bottom: Bearing of the currents over the same time period.

Each tick corresponds to an approximately 10-hour period.

The grey area indicates the central eight hours during the cyclone.

A small difference in average pressure is observed between the two ADCPs throughout, reflecting slightly different deployment depths. There is also a very slight gradual increase in pressure/depth over the three‑month deployment; this can be seen in the lower panel of Figure 4, and corresponds to about 40 and 30 cm for C0A and I0A Origin 600s respectively.

This is unlikely to be caused by inherent sensor drift; indeed, on‑site inspection by divers at the end of the campaign confirmed that the bedframes had sunk relative to their nominal deployment depth, accounting for the observed increase in average pressure. Improved bedframe design may help future deployments guard against such challenges presented by a sandy bed, such as at this site.

The bottom plot shows the pressure data converted to depth, with the legend showing the time‑averaged depth. In the bottom plot, the solid blue and red dots at the start and end of the timeseries show the small increase in depth over the deployment.

Biofouling

In warm, shallow coastal waters, biofouling can lead to a degradation in ADCP performance. Figure 5 shows one of the Origin 600 ADCPs with its external battery canisters prior to and after deployment. Despite a substantial level of hard biofouling from the growth of barnacles on the transducer faces, the ADCP current measurements did not exhibit any substantial noise increase over the deployment period. While this problem would ultimately degrade the data over a prolonged exposure period (and potentially damage transducers), on the several‑month timescale of this deployment the data maintain excellent quality. If biofouling is a concern, there are coating options available.

During recovery of the Origin 600s, it was discovered that one of the ADCPs had been buried under sediment deposited during Cyclone Kirrily. Remarkably, this burial did not substantially affect the quality of the data, as can be seen in Figure 2. However, the backscatter intensity data from that period does show a gradual decrease. While this could correspond to natural changes in sediment loading, it is also possible that this is caused by biofouling, resulting in weakening of the acoustic signals used by Origin 600.

The latter shows significant amount of biofouling.

Summary

The deployment of two Origin 600 ADCPs at the AIMS site demonstrates the capability of the device in challenging conditions over a multiple‑month campaign. Current and environmental data from both devices are consistent with each other and show little evidence of performance degradation, in spite of substantial biofouling and sediment burial. The ability of Origin 600 to accurately measure currents in shallow (8 m) water highlights the flexibility of the ADCP, which also excels in depths up to 60 m and beyond.